Scott talks shop with Adam Nayman from the Directors Guild of Canada. Check out the five-page spread below.

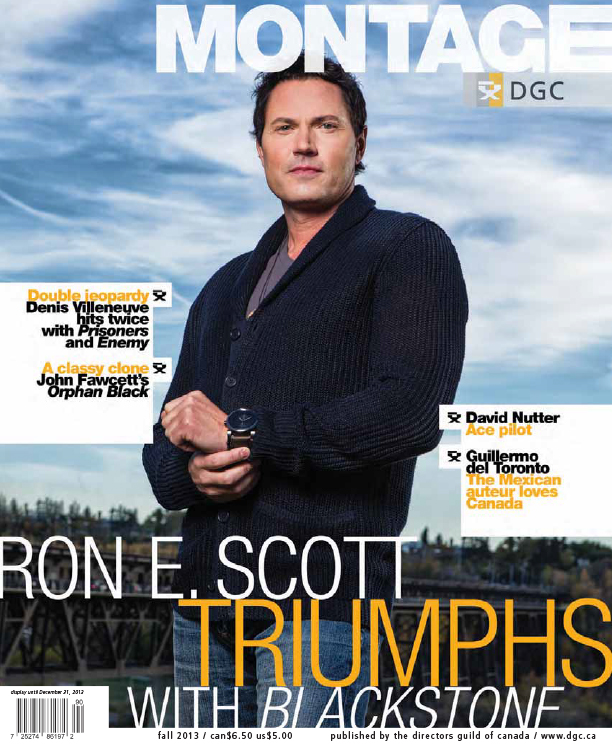

BLACKSTONE’S RON E. SCOTT TALKS SHOP

Written by Adam Nayman

The opening title sequence of the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network’s (APTN) hit series Blackstone unfolds to the rhythm of a children’s chant: “One little/two little/three little Indians.” The imagery is sinister: vintage black and white photographs of Aboriginal Canadians, overrun by creeping graphic overlays that suggest the landscape has come to life to swallow the people whole. This is “Ten Little Indians” by way of Agatha Christie, or maybe David Simon, rather than Mother Goose: a nursery rhyme reconfigured as a nightmare.

“Some people love ‘Once upon a time,’” says Ron E. Scott, Blackstone’s executive producer, writer and director. It’s unclear if he’s referring specifically to ABC’s hit prime-time series, which offers a glossy take on historically Grim(m) myths, or the general appeal of fairy tales, but watching a few episodes of Blackstone confirms that the Edmonton native isn’t much for glass slippers or Prince Charmings. Shot on location in Alberta, Blackstone is a rugged little beast of a series about the fictitious Blackstone First Nation, whose reservation is a hotbed of corruption, collusion and barely restrained violence. The well is contaminated, both literally and figuratively. Not only is the environment rotting but so are several of the characters.

“They don’t take BBM ratings on reserves.”

Blackstone isn’t the first Canadian series to depict life on a First Nations reservation. CBC’s The Rez adapted W.P. Kinsella’s short-story collection Dance Me Outside into two seasons’ worth of award-winning television. But Scott sees his show as part of a different tradition. He isn’t taking up the mantle of Canadian lit but rather trying to retrieve the gauntlet dropped by the heavy-hitters of American premium cable. He says his three biggest inspirations are The Wire (for its complex narrative), The Sopranos (for its willingness to present audiences with anti-heroic characters) and Friday Night Lights. “That one,” he says with a laugh, “at least has an aspect of hope.”

It’s possible to see those little glimmers of humanity amidst the misery on Blackstone, which has the heightened pace, and modest production values, of a soap opera but makes an admirable attempt to remain rooted in reality. Season one revolves around a skewed tribal election; season two has an environmental focus. Alcoholism, drug abuse and child molestation are depicted, but never sensationally. “I don’t think anyone has taken the risks we’ve taken with Blackstone,” says Scott. “No other storytelling has been this aggressive. It’s all ripped from the headlines. All of the arcs and themes are based on true stories.”

The show’s detractors might argue that, rather than cutting too close to the bone, Blackstone misses the mark entirely. In an article published in The Winnipeg Free Press after the series’ premiere on Showcase and APTN in late 2010, Colleen Simard describes the complaints of various First Nations leaders that the show “reinforces stereotypes: the lazy drunken Indians, the easy women, the corrupt chiefs and councils.”

“Someone might watch half of the show and write an editorial about the whole series,” offers Scott in response. “On the surface, it’s easy to criticise but if you watch the whole show it might change your mind. The CEO of APTN was at a convention with a lot of chiefs, and they either liked the show because it was promoting conversation or they didn’t like it because it challenged them. It’s led to discussion within reserves about changing bylaws. I’m shocked when I hear stuff like that, that a television show is contributing to social change in a system that’s flawed even at the best of times.”

Blackstone is also a product of a flawed system: the Canadian television industry, which hasn’t always had a place for this kind of programming. “There’s been a shift in the broadcast world,” Scott says. “Nobody is taking risks. They’re playing it safe with their shows, so they can air on five networks and be repurposed. We’ve discussed the show with all the usual suspects—CBC and CTV—and they respect what we are but it doesn’t line up with their mandate.”

Scott says it took nearly 10 years to get Blackstone made. “It started as a movie of the week [MOW] that was being developed by Gil Cardinal. He came to me as a content creator and said he had a movie to get done. I knew that MOWs were sort of dead in the water in Canada after 9/11, so I said I’d be more interested in trying to develop it as a television series. From there, we shot the pilot and APTN said, ‘Yes.’ I started to put my fingerprints on it.”

APTN obviously liked the idea of a show featuring primarily Native characters, and the fact that Blackstone had a little bit of edge to it augured well for its popularity on a network whose shows could sometimes be blandly affirmative. The darker qualities also appealed to Showcase, which Scott recalls as being “the leader at the time in sort of indie, edgy television.” And then? “And then Showcase moved away from that and APTN stuck with us. And it’s been their top-rated show since then.”

“I don’t think anyone has taken the risks we’ve taken with Blackstone.”

Ratings are a difficult thing to talk about with a show like Blackstone because, as Scott says, “They don’t take BBMs on reserves.” The fact that the series’ first two seasons are also available to stream online on APTN’s website (aptn.ca) similarly complicates the question of who’s actually treating Blackstone as weekly appointment television and who’s binge-watching it, but such is the nature of 21st-century entertainment. (For example, Orange is the New Black is getting reviewed as one of “the best shows on television” even though it’s only available on Netflix.) Scott says he trusts the word on the street when it comes to Blackstone’s popularity. “I can guarantee you if you go onto a reserve, nine times out of 10, they know what the show is all about.”

The mainstream has taken some notice. Michelle Thrush, a Cree Native who appears in French director Arnaud Desplechin’s TIFF 2013 selection Jimmy P: Psychotherapy of a Plains Indian, was a surprise winner of the Best Actress Gemini in 2011 for her work as a woman coping with the death of her daughter. “We’ve been nominated for 25 awards and we’ve won 22,” says Scott proudly. He knows his show is a cruiser-weight next to other, more top-heavy network dramas, and he likes it that way. “We are a small show,” he says. “We don’t hide the fact that we have budget challenges, but we do what we can and I think we’re putting out a strong product.”

At the same time, Scott says he hopes the next set of episodes will find Blackstone branching out a little bit, especially in terms of its narrative. His model may be The Wire, but the show has a long way to go before it reaches that sort of head-spinning cause-and-effect complexity. “Season three has been crafted a little bit differently. It has a bigger feeling to it. Season two dealt with foster families and water problems on reserves. Now we’re moving into corruption in the police department and city hall. We want to offer some commentary on how criminal justice works in the Native community. I think we’re asking some big questions.” He admits that it can be difficult to balance the quest for realism against the template of steadily escalating drama that makes a show like The Sopranos so addictive. “We’ve had political consultants for the first two seasons, and we’ve always made an effort to be as authentic as we can. At the same time, it’s a fictional show on a fictional reserve. It’s not a documentary.”

As Blackstone’s creator-writer-producer-director, Scott is accountable for more than the series’ reputation. He’s involved at every level of the production. “The term I use is ‘Blackstoned’ because I’m in so deep, it’s scary,” he says. “For the duration of the shoot I’m consumed with every aspect of production. We block-shoot a serialized series so everything ties to everything, and it’s so layered that focus and detail are critical. What always fascinates me is on a serialized TV series you create these intricate and dimensional characters that arc over several episodes on the page, but when you add the talent—‘the skin’—they inspire and expand in ways I could never imagine.”

Scott says that making Blackstone is a physically draining experience, not that this stops him from getting his reps in at the gym beforehand. “I wake up two hours early and have a short workout to prepare for the day. I’m mostly focusing on execution and what scenes are being shot, and also where I can gas and brake to get the day. So much of a shoot is based on weather, which actors were up and how big the scenes are. In my trailer I polish every scene and if necessary rewrite or rejig, based on what happened earlier or what we planned later in the story world. On the day, the actors are free to discuss and workshop anything they feel is critical in their world. It’s an aspect of Blackstone I really appreciate.”

One of the most notable things about Blackstone is its commitment to using local and indigenous actors. “We do that as much as we can,” he says. “During a season we have as many as 70 or 90 cast members. This year, we used 12 Native actors with no previous experience. I want Blackstone to give people hope, the feeling that if they want to be an actor, they can get on the show.”

The cast includes its share of familiar faces. The great Gary Farmer (who also was on The Rez) plays transplanted university professor Ray Lalonde, while Hollywood vet Eric Schweig brings his usual gravitas to the tricky role of Blackstone’s dubious chief, Andy Fraser. Season one also featured a plum role for the late Saskatchewan icon Gordon Tootoosis, to whom season two was affectionately dedicated.

“The term I use is ‘Blackstoned’ because I’m in so deep it’s scary.”

That Blackstone occasionally feels like an actor’s showcase may have something to do with its creator’s own thwarted thespian background. “I started as an actor in Vancouver,” says Scott. “I was there for years but it never really clicked for me. I did film school in Vancouver, where I was able to learn the craft. I produced a feature, directed some shorts and music videos, but I just sort of hit my stride with scripted shows. I created four scripted series, but Blackstone was the pinnacle for me. It was an hour-long drama with some creative latitude. As a writer-producer-director, it’s just been a dream.”

Scott’s previous series, Mixed Blessings, was about a romance between a Ukrainian man and a Cree woman living in Fort McMurray—a comedy predicated on culture clash. The tone was much lighter than Blackstone, but Scott can see a connection between the two shows, and also a theme that runs through his work in general. “Because I’m Métis, I think I have a desire to comment on the idea of two worlds at once,” he says. “I have green eyes but I’m Métis and also part Cree. I think the ability to see two sides of something at the same time is important to me, and something I like to reflect on. There is a non-Native aspect to Blackstone as well. I want to have some insight into that split.”

Identity crisis is, of course, a major theme in Canadian arts and entertainment—every year a new movie or book comes along to analyse our two solitudes— but Scott seems to have a pretty good idea of who he is and where he belongs. He wants to keep working in Edmonton, and not just because he “bleeds Oiler Blue.” He simply doesn’t think that a show like Blackstone could work if it were produced in one of Canada’s industrial epicentres. “I’m regionally challenged,” he says with a laugh. “But I understand what’s going on out there. I read the rags. My family is here, and happily I’ve been able to keep doing what I’m doing out here.”

Adam Nayman is a Toronto-based film critic for The Globe and Mail and Cinema Scope. He is a regular contributor to Montage, POV and Cineaste.